I’m doing 4 things a day now.

Having tested it for three weeks, I believe this to be the correct number.

AUDIENCE: How does it work?

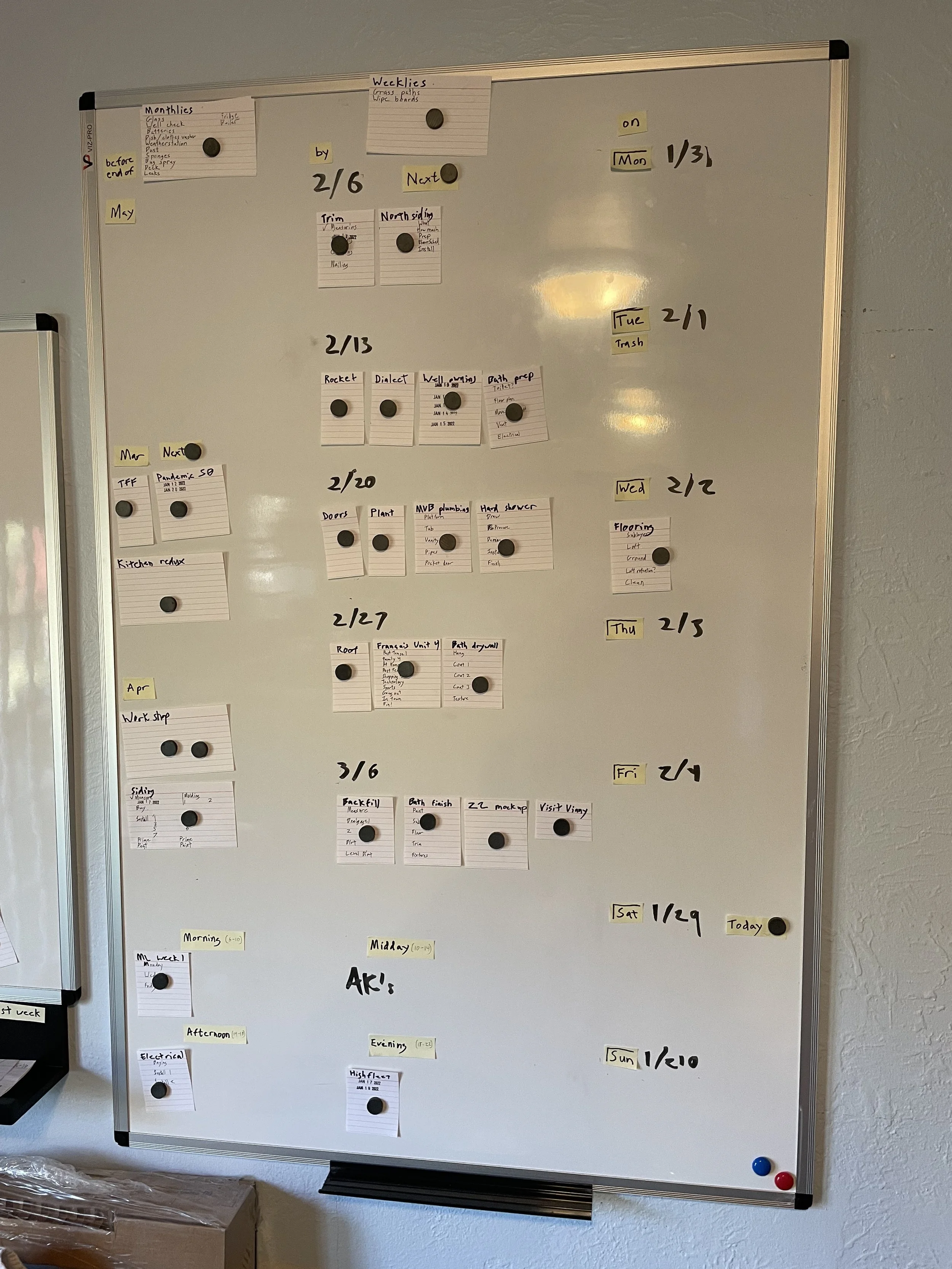

Get a big white/black/corkboard. Put all the things you want to do on it. Arrange them as desired: we’re currently working on construction projects so a due-date calendar view makes the most sense.

A white/black/corkboard with magnetized index cards on it.

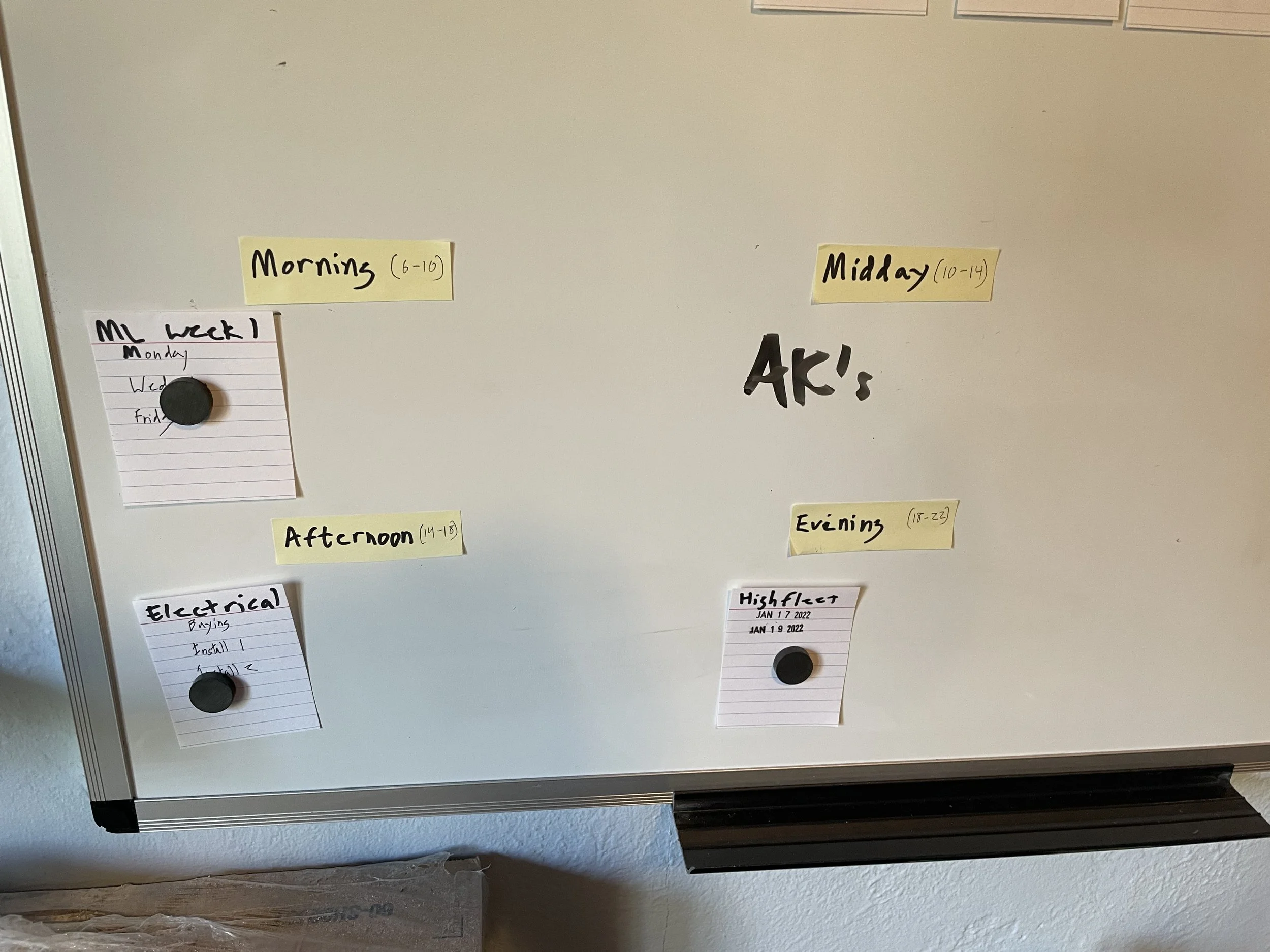

In the morning when you wake up (or the night before if you’re feeling particularly organized), pick four things you want to do that day. Place each thing in one of the following blocks (time provided subject to sleep schedules and other alignment restrictions):

Morning - 6 to 10am

Midday - 10 to 2

Afternoon - 2 to 6

Evening - 6 to 10pm

During each block, work toward satisfaction of the thing you have chosen. A lot of the time this will be taking a bite out of a big thing that will take multiple bites to digest fully; I recommend developing a block-level objective to aim at in these cases, for improved focus. I do this currently by writing the Thing at the top of an index card with the block objects below it. This method also gives you something to check off at the end of a block, which is always nice. If you go this route, buy a date stamp to go with it: very satisfying to kachunk your way out of a job, and you get to see all the days you’ve made progress on it.

A 4 hour block is a durable length of time: nothing short of a catastrophe can truly disrupt it. It’s spacious enough to keep you from staring at the clock, subdividing it into useless minutes the way shorter periods like an hour or two would (and did in my previous schemas). I miss the exact start and end times on blocks all the time and even after adding in law-of-averages fixed costs like prep, tear down, journaling, eating, et cetera a block always provides two-and-a-half-plus hours of quality doing-a-thing time, which is enough to make material progress on anything.

If something unavoidable comes up (phone call, needing food, rapid onset nap), take care of it and resume. However, if you can, defer and add it to a list of to-do-later’s. When you have stray thoughts about other things you want to investigate, add those here as well. I call this list the Checkboxes. When you get enough things in your Checkbox bucket to fill 4 hours, assign that its own block and burn through them. The Checkboxes remain a nearly unaltered cornerstone of my methodology after a hundred schemas; they act as a sieve, bulletin board, and organizer all at once. If you haven’t done this kind of deferred task aggregation before, you’ll be taken aback by how many of items you’ll scratch off without further action: things you thought you cared about just because they crossed your mind but, pulled the slightest distance from their origin, don’t matter now. The rest of them will likely bundle into categories, ready for systematic disposal and possibly even offerings to the false prophet Multitasking, which is only ever really good for dealing with stop gaps and other minor tasks...like the ones you’ve listed here. Some of those idle considerations you jotted down might blossom into Things all their own once you give them a few minutes’ consideration. However the items come off the list, the static will be flushed out, and you’ll be free again to concern yourself with the stuff you actually want and need to spend time on.

YOU: That doesn’t seem like a lot of things to get done every day.

So that’s what I thought at first too. I developed this strategy during winter break as a reprieve to recover from burnout. 4 hours per task was enough time to keep the paranoic lobes of my brain from running into the walls, wearing me down further, and concentrating on just 4 things a day seemed like a slow enough pace to sustain until I was back to 100% (or 85% at least).

As happens in experimentation, the most important lessons are lurking just out of focus. I’ll admit that doing 4 things a day, even if you’re making solid progress on each of them, isn’t very many. But what about 28 things a week? Or 120 things a month? I would consider a hundred-notch month to be outstanding even by manic standards, and you can get there from here adding a measly 4 a day. Who couldn’t pull that off?

The key is to stop thinking about days as checkpoints. Days are just days. You don’t need to go to bed every day thinking you “got everything done”. That’s way too much pressure. It compels you to stuff days full of minor concerns to get a handle on things that would need less scotch tape if you handled them in their own time, grouped and synergized with like activities. Instead, treat days as what they are: an Earthly rotation during which you need one good rest (which is already accounted for in the schema).

YOU: What about stuff that “studies show doing this every day” is the best way to do it?

You didn’t happen to hear that from Duolingo or Headspace, did you (both of which I use and think are great, to be clear)?

Like most things in the modern economy, ease of attachment is the apex priority in product development: you either grab the consumer and habituate them to your platform or you’re left in the dust. The easiest habits to build occur with extreme regularity (daily) involve little or no effort (5 or 10 minutes a day) and give you an immediate pro-social reward for completing them (notifying all your friends while an orgiastic display of “you did it” style fireworks and smiles gets plastered over your screen for standing up when the watch told you to).

Habits are fine: obviously if you don’t actually do something it doesn’t get done, so step one there matters quite a bit. Habits can also reduce the cognitive load and thus willpower you use on maintenance activities, which are their primary domain. You don’t want to spend anymore time to feel healthy or informed or organized than needed unless the act of doing so is itself satisfying. This schema itself is technically a habit.

The trouble is that habits are also by definition an automatic process. They are something your brain is hardwiring into place for ease of future retrieval, and daily habits are designed on purpose to be as trivial to wire as possible. What are the odds an automatizable activity will be the best way to accomplish (let alone experience) something that you want to DO--by definition a manual process?

Engage with one thing, fully, for a comfortable length of time (say, four hours). It’s much more satisfying than the 4 to 6 out of 10 emotional hum of bouncing around between a thousand middling wants trying to keep all the bars filled up.

YOU: What counts as a thing?

Generally it’ll be pretty clear what the thing is binding a subgroup of activities. If you’re building a terrarium, the terrarium would be the thing. A video gaem is a thing (this system isn’t just a workaholic paradise, though it does admittedly have a strong bias against certain kinds of leisure that I’m comfortable saying aren’t worth your time). Keeping in touch is a thing. Getting jacked is a thing, though it might be a good candidate for the following exercise.

Sometimes you’ll have an idea for something to work on that won’t readily absorb 4 hours. When this happens, embrace the creative constraint by asking yourself what lives around the margins or in the same universe as the activity that would make it a more complete experience. You can do this with virtually anything. Short movies have production backstories to investigate; good workouts are made outstanding by expanding them into a holistic maintenance of the body. You’ll likely recognize opportunities for growth in these smaller things that wouldn’t occur to you if you confine your aperture to the exact thing you were aiming to do.

If you really can’t figure out how to expand it--if this thing isn’t worth 4 hours of your time--maybe it’s not worth doing in the first place? Perhaps you’ve convinced yourself out of a sense of discipline or shame or need to signal to others that this is a thing you need to do. I promise: if you’re staring at the right goal, you’ll figure out how to accommodate it within this structure. Your mind will push you to do so. If not, I recommend putting it in the Checkboxes for additional processing.

YOU: I can’t dedicate a quarter of my time to working out/learning a language!

1 - If you really wanted to get jacked or fluent: yes you could, and you would.

2 - You don’t have to! Just do it every other day, or every three days. The number of things that are best done every day, let alone require daily attention, is vanishingly small. Don’t focus on days.

YOU: Can I do one thing for multiple blocks in a day?

Yes, but I recommend putting a break block between them. One of the reasons I stopped at 4 things a day instead of 3 or 2 (though I may try 3 soon just to see) is to make sure I don’t accidentally burn myself out intraday. Mental energy and focus isn’t like a reservoir of water you fill back up; it’s more akin to a field of soil that needs to rotate crops to stay fresh. As long as I’m not pushing myself too hard (which shouldn’t be necessary when you’ve got swathes of time like this) and the two activities are dissimilar enough, doing the one won’t tax my ability to do the other and can even realign a crooked headspace produced by stewing on one thing for an extended period.

YOU: What about breakfast / getting ready for bed / that one thing that always happens on Tuesday

Do that stuff and get back to the Thing. Or make a schedule that fits whatever nonsense you have going on. I’m not going to give you a bad grade for diverging from this plan I made up and will certainly alter next month.

YOU: Don’t you work an 8x5 with meetings and such? How does this jive with that?

I tell my boss what I’m doing on Monday, and do it during the week in blocks I assign to work on those things: time I make much better use of because I’ve carved it out for the purpose. If there’s a meeting I can’t miss or move inblock, I suck it up and attend offblock. I’m on-call from 9 to 5, but I’m not engaged from 9 to 5. Having worked with many companies, judging by the quality of their work: neither is anyone else. I get uniformly stellar performance reviews.

YOU: There’s no way my boss would let me do this / I work in an office.

Sounds like your job sucks! Sorry about that. You should quit and work somewhere that respects your time. Alternately, you should send your boss this article (https://www.npr.org/2019/11/04/776163853/microsoft-japan-says-4-day-workweek-boosted-workers-productivity-by-40) about how working a full day less every week INCREASED productivity at Microsoft’s Japanese headquarters.

YOU: You’re only able to do this because you’re an autistic white man with no dependents that doesn’t watch TV.

I know, right? Pretty awesome! Anyways, see you next time.