A Love Letter to the Breach

Today I’ll be talking about the February 2018 video gaem release titled "Into the Breach”, which I shorten to “Breach” from here on for the sake of pacing and because the Freudian slip is too good to pass up. When forced to choose between double entendre and double preposition, I shall not hesitate to choose the foreplay.

Mechs are cool, good mech gaems are rare, and the dev duo at Subset has followed up FTL with a second gold standard experience rendered from scratch. Praise has been heaped on Breach outside these walls, and on the major points (themes, music, the dance) I’ll cosign what’s already been said. Anyone with a PC and a spare weekend should get to know this gaem on some level. However, I think a tendency to compare things to one another oversimplified the critical narrative surrounding Breach. Is it a spiritual sequel to FTL? Is it environmentally informed chess? Is it a less random XCOM? It is a small scale Advance Wars? Is it the sum of these comparisons with mechs? No. When Breach gets shoved into these boxes for rhetorical expediency, we bury a magical property it doesn’t share with any other gaem I've played.

I explore that magic to the exclusion of all other subjects here, using the common references to dig into how Breach differs from them once the most obvious comparisons are placed to the side, starting with XCOM’s tension, moving to Chess’s austerity, then Advance Wars’ scale, capping on an paternal confrontation with FTL. My hope is—with a bit of subtractive quadrangulation—this sparkle in the back of my head will have a name. To be clear: I’m not dunking on these titles (other than maybe chess). I sorely miss Advance Wars, and the only gaem from 2012 better than XCOM was FTL. This isn’t about Breach exceeding its brethren (or dad). I just think it’s special and would like to be able to say why.

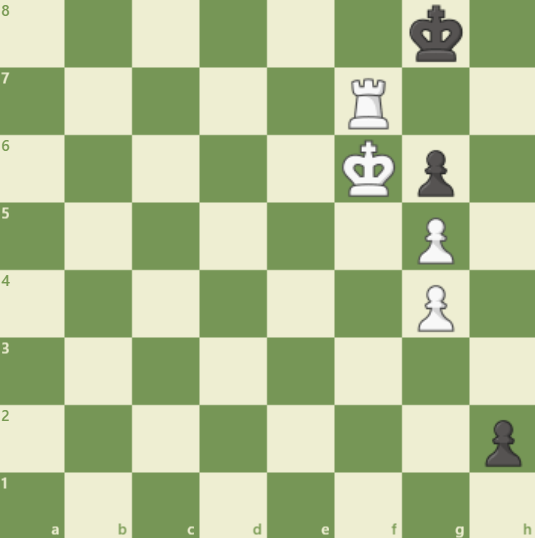

First, the subject matter out of context. Breach puts you in charge of three time-traveling mechanized pilots holding back swarms of humanity-ending bugs called the Vek. Each turn, Vek bust through the ground in the southeast, move toward civilian structures in the northwest, broadcast an attack plan for the next turn then freeze, at which point it’s on you to minimize the oncoming damage. This happens on a claustrophobic 8x8 grid, with overlays of arrows and numbers explaining exactly what your commands will accomplish and what the bugs will do in response without an ounce of give anywhere in the forecast. Every round is a procedurally generated puzzle with no bespoke solution: a kind of Minority Report-flavored triage.

When you first start playing Breach, you’ll be tempted to directly murder your way to victory, but this is only the most obvious (and honestly least effective) strategy at your disposal. As you burn through timelines and pilots, a gaem of inches rather than hit points comes into focus. Your moves don’t thwart the Vek’s intentions—they reshape them. A Hornet will attack the tile in front of it when time unfreezes whether that tile contains a skyscraper or one of its teambugs and a nudge makes all the difference. The web of systems you rely on for this reshaping is enormous. You might have artillery that can push the Vek into each other, grappling hooks for dragging them into water, cannons that freeze them solid, smoke bombs, rocket launchers and rock launchers, all of which work together in curious ways so that when you hit “END TURN”, the Vek hit anything except what they'd set out to destroy. Each map challenges you to pull this off four turns in a row and, though you can’t always make it out unscathed, I’ve never played a gaem that rewards an extra minute’s consideration as reliably as this one. With three allies and at most seven enemies to consider this sounds like it would become a trivial operation after a few hours, but keeping things straight is so daunting you’re allowed to “RESET TURN” once per map. Dwell on that for a moment: the people who coded FTL (a gaem that borderline prides itself on spontaneous cruelty) made a gaem where you have perfect insight to the consequences of your actions with no time pressure, and decided you deserve a mulligan every 4 turns, regardless of the difficulty setting.

Your objective throughout the gaem is to keep the power grid alive, abstracted as a box with 7 orange bars permanently housed in the upper-left of your console. When a structure falls, one orange bar shorts to black. If you keep the lights on, the Vek will retreat and you can proceed to the next 8x8 map. These maps form islands, and if the grid holds over the course of two to four of those islands, you'll earn the privilege of blowing the Vek off the face of the Earth…in this timeline, anyway. That cycle takes from 10 minutes to 3 hours depending on your ambitions and competence as an insecticidal strategist.

Reference gaem number 1: XCOM (the modern era titles starting with Enemy Unknown, which I’d guess are the wider communal contact points with the series)

XCOM has you corralling the might of human ingenuity and desperation to resist technologically superior space invaders. Play occurs in two layers. First, a strategic home base layer where scientists and engineers pore over the spoils of war trying to give humanity an edge. Second (and our focus here), a tactical combat layer where small teams of commandos inch their way across crash sites. Because the gaem relies on chance-driven dichotomies between hit and miss, your role as commander is less about creating a plan than it is about correcting course as that plan falls apart. These campaigns for the future of humanity are long—dozens of hours if you don’t screw up early—which combines with the luck factor to give XCOM its reputation as a real fucker of a gaem. If Firaxis would hire a few more QA testers, this reputation might even be earned, but *both* the new XCOM gaems came in so hot I am going to waste a sentence here reminding everyone how bugs turned their iconic Hardcode mode into a middle finger to the audience for months after release. Finish your goddamn gaems, Firaxis.

Anyhoo, XCOM and Breach have almost the same theme: save humanity from an existential alien threat using turn-based squad combat. That mirror image description belies a mirror image contrast in how the two gaems actually work.

In XCOM, misfortune is the real enemy. Critical fire will lay down squadmates you’ve been relying on for days; an operative will stuff their rifle barrel into the geometry of a Sectoid then almost T-pose out of the way to show how an 85% chance to hit didn’t pan out. You’ll learn to love the precious few weapons that always do what you intend, such as—in what feels like knowing irony—grenades. When you can’t get away with those certainties, you cross your fingers, swear under your breath, and improvise as necessary.

Breach demands no such fatalism. On Normal, with any pre-constructed set of mechs, the gaem is yours to lose. Not entirely due to a lack of randomness, mind you…Breach has die-rolling too. You don’t know which Vek you’ll be fighting or where until they emerge from the ground; the CEOs who rule the islands don't tell you what weapons they have on offer until after you save them, concealing most of the loadout strategy layer behind a time wall. We don’t register this as luck because we tend to ignore what I'm going to term environmental uncertainty. You know what's going to happen when you push a button in Breach but the gaem dictates the circumstances in which you push it—emergence points, bug types, map layouts and so on. You don’t know what environment you’ll have to negotiate. XCOM has a mountain of environmental unknowns too, particularly on your first run through the story, but you’re not only caught off-guard by your circumstances…you can't even be sure what will happen when you make a decision. This more familiar form I dub performative uncertainty, to describe a gap between your desired act and the one that occurs. Can you be sure that Muton will stop being a problem if you shoot at it? Not until it hits the ground. Will grabbing a Vek and judo-flipping it behind you into the water be the most satisfying thing you do today? Rest assured it will be.

This difference in unknowns dictates everything about how these gaems play. Problems in Breach are presented whole cloth at the start of each turn and you’re given three decisive moves to solve them. Problems in XCOM can emerge at any time and have to be handled with whatever actions you have left to use, anywhere from six to zero depending on the state of your crew. This is only the start of it, though. Whatever solution you arrive at in Breach will work exactly as intended, assuming you didn’t flub the logic. In XCOM, it’s possible your first fix to the problem won’t work either, or your second, compounding the initial conditions. You don’t know the true scale of the problem until it’s behind you.

Does that make XCOM’s combat more tense? On balance, yes, but that’s not all that goes into making a fight satisfying. Your actions in XCOM arise from and are subject to precarious circumstances. This incentivizes slow, methodical play: crawling from cover to cover, snipers in overwatch. The original release of Enemy Unknown let you take as long as you wanted to complete nearly every mission, and everyone I know took about as much time as they could stand because it reduced their exposure, mitigating the cost of failure. Firaxis partially thwarted this tack by adding time-sensitive objectives in both the expansion and the sequel, but these stratified the problem in my experience rather than solving it a lot of the time. I started adding a rogue runner to my teams whose job was to retrieve, blow up, et cetera whatever geographically distant object was responsible for the time crunch, leaving the rest of my team to proceed with the steamroller strategy. In short, XCOM’s version of randomness discourages aggressive behavior. Breach has no such mechanism for punishing ambitious maneuvers. It can take a few minutes figure out what you should do, but there is no scenario in which the answer is “cower in fear of the unknown”. You get in there and deal with as much of the threat as you can each and every turn. In the world of minmaxing, XCOM is about min and Breach is about max.

Why do I blame the “version of randomness” in XCOM rather than randomness itself? Because Breach hints at another way with its only designated random event: the city defense. There’s a small but non-zero chance a building will resist an attack from the Vek, on the order of 15 to 30%. You can’t count on it, but it’s great when things fall your way (so to speak). The animation even characterizes this as heroic rather than lucky, with a green anime sheen protecting the building rather than the Vek swiping to no effect. The one performative unknown in Breach is a positive, possibly run-saving, event. Compare this to XCOM’s parade of inconvenience, in the 80 to 95% range, where most things go as planned but not all. Chance events in XCOM are an unwelcome frustration; in Breach, they’re a pleasant surprise. What would an XCOM driven by positive rather than negative outcomes—where you don’t expect things to work but sometimes they do—feel like?

Breach doesn’t answer that question, opting for the path of procedural certainty (above caveat excised), an experience that can ratchet down the error tolerances because every misstep is on you. Is that certainty what Breach makes special? Let’s test that premise against another gaem.

Reference gaem number 2: Chess.

The touchstone of strategy gaems. Chess marries arbitrary rules of motion to a small square grid in a way industrial quantities of artificial intelligence has yet to solve. It’s been around forever as far as gaems are concerned and everyone understands how it works on a conceptual level if not a mechanical one: always stay one move ahead of your opponent. Chess is the original e-sport. Throw a football at a convention and you will hit someone willing to rank the thrill of a discovered check and a touchdown on the same tier. I believe this attitude partially explains my bias against the gaem (that and I’m not very good at it).

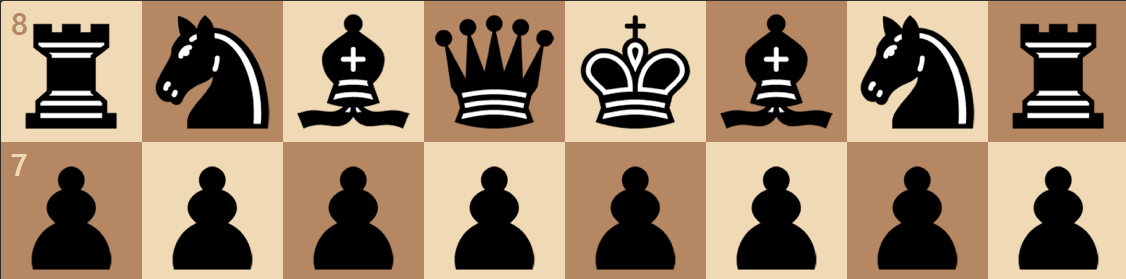

Chess and Breach are both turn-based strategy gaems played on an 8x8 grid. These two are constantly compared to one another—the devs even patched in chess-style algebraic notation for describing the action—but most people use this comparison to compliment the depth of Breach’s tactics rather than describing a real affinity between the two gaems.

Breach is a confluence of systems where chess rigidly applies just a few. Chess has 6 unique pieces, 1 starting condition, 1 objective, and a handful of special circumstances (check, castling, en passant, promotion). Breach has 24 mechs, 16 pilots, 82 weapons, fire, water, acid, mountains, civilians, time pods…in short, a play field whose combinatorial capacities outstrip chess by orders of magnitude. Breach is a gaem about staying exactly three moves ahead of your opponent—one for each mech—and those moves are informed by a superstructure alien to the chess board. Your turn-by-turn goal isn’t just to position yourself to trap a king piece, but rather to reach an optimal compromise between pushing the bugs off your buildings, completing objectives, and not losing pilots.

This only describes the vanilla experience, of course. The mere task of winning Breach stops being the point once you’ve got the flow of the run down. Earning the 45 achievement badges are where it’s at after that. An example: absorb 5 points of damage with armor on a single map. This is a tough scenario to contrive and it can be counterproductive to success, distorting the lines of the systems in cool ways while teaching you about how they interact. You learn that armor doesn’t block explosions, fire or collisions; that acid compromises it. You start to trust armor to take hits for you and, by extension, to rely on the integrity of your mechs more when deciding where damage should be allocated, even after you’ve finessed a scenario enough to earn the badge. Chess is played under special conditions to imitate this—chess puzzles have quite a heritage, in fact—but it has nowhere near the mechanical breadth on which to build them. The gaem is hard because the pieces move in strange ways, not because the whole thing is all that complicated.

I'm not saying Breach is more sophisticated than chess. In fact, such a claim would be pointless because of a third form of uncertainty only relevant to chess. Where XCOM’s is performative, and Breach’s is environmental, the black box of chess is motivational uncertainty. You have an opponent sitting across from you whose internal logic is, on some level, mysterious to you. Driven by their knowledge of the gaem, the state of their mind, and a recursive reaction to your own play style, they will choose to move the pieces. You might be able to predict what they’ll do on occasion but if you could reliably figure it out (or ignore it by implementing a dominant strategy) chess would devolve into a technical drill…in many matches between asymmetrically skilled opponents, it does. The chess board always starts in the same configuration (no environmental unknowns) and the pieces act in a reliable way (no performative unknowns). The only thing distinguishing one chess gaem from another is your opponent, which is quite rare for board gaems.

Did I just waste two minutes ginning up an uncertainty subtype that says “yo, this gaem’s multiplayer”? To a degree, but I think it’s important to see what having an opponent you can point at does to a gaem. It gives chess an organic depth that can’t be practically mined and goes a long way toward explaining its staying power amid a vast graveyard of multiplayer gaems, both older and newer than chess. Even when one side or both is played by a computer, these unknowns don’t entirely disappear (assuming a decent algorithm pulls the strings). These distinctions between uncertainty subtypes are, of course, thresholds in a continuum I’ve marked off for convenience rather than some hard fast rule about the nature of the unknown, but if the Vek can are in some sense motivationally uncertain, it’s a weak form of it. Their ability to surprise a veteran player by action is very limited.

So then, if chess is so deep and everlasting, why play Breach? For just the opposite reason: it’s flashy and superficial. Divorce those words from their pedestrian derogatory usage for just a few here. In my time as a bad chess player, I’ve had a few “Aha!” moments, where the clouds part on a seemingly hopeless board: a knight here to capture a crucial pawn with a set up for that previously scorned discovered check. These moments are undercut by the actions of the enemy. In thinking one move ahead of your opponent, their moves are staggered between yours. Your master plan might succeed, but it does so slowly and uncertainly over a span of time. Breach doesn’t hold you up that way. You might spend five minutes poring over the systems and the positions, weighing options in a dire setup but, if the light bulb goes off and you see the perfect play, you are instantly permitted to pop smoke on that mantis, displace the crab, then shove that beetle in position to dunk its ass in the river (seriously, that might be the best feeling in the turn-based genre) all as soon as it occurs to you how to pull it off. Breach’s epiphanies are frequent, bombastic, and the systems both make them harder to see from the jump and feel more novel overall. Is it more satisfying to slowly master another player or to seize many splashy victories? This is a personal question and the answer probably depends on how much of a jerk you are.

So is that the magic: putting an aggressive plan together and executing it rapidly with confidence? Not quite. I think there’s still something else going on here, and we need to expand the scale of this conversation to explore it.

Reference gaem number 3: Advance Wars

Advance Wars is a combined arms territorial control exercise where land, air, and sea forces work together to capture a region. Combat revolves around rock-paper-scissors-style tactical triangles:

Battleship > Cruiser > Submarine > Battleship

Battle copter > Rocket behind mountain > Anti-air > Battle copter

If you build your army out smartly and position them well, you’ll eventually punch a hole in the opposing force wide enough for Infantry > Headquarters. The macro and micro layer of the gaem are one contiguous mesh with unit-constructing bases and revenue-generating cities operating in the same frame as tanks and bombers. Like chess, Advance Wars is governed by the motivational uncertainty of opposing commanders but varied terrain gives it a lot of environmental uncertainty as well.

The smallest map in Advance Wars is substantially larger than the only size map in Breach, with several times the head count in climactic moments. This permits a wide range of mobility, with varying speeds and domains. Breach’s mechs, varied in loadout as they are, mostly follow the same rules of motion: three to five spaces a turn, cities and mountains impassable even by flying units. In Advance Wars, infantry can scale mountains, tanks can drive through forests at half pace, landers are the only boats allowed on beachfront tiles, and fighter jets move more than twice as fast as submarines (which doesn’t sound terribly impressive in a vacuum, but that delta well exceeds the ones found in Breach).

The tactical triangles are also unique to Advance Wars. Mechs in Breach might be better or worse equipped to handle a situation, but few of them are ever entirely useless: all units exist in the same plane with the same kind of armor and even a mech posing no direct danger to a Vek can probably be the one in a one-two punch against it. By contrast, four tanks are as useless as one against a bomber in Advance Wars (some spacing techniques notwithstanding). The bigger playfield permits combat limitations like this, which in turn broadens the dynamic range of the fight.

Does that breadth make Advance Wars more interesting? Yes, but the size of the possibility space isn’t all there is to a satisfying sortie. Advance Wars is at its best when you’ve got a joint strike force on the verge of a breakthrough. Your opponent has tipped too much of their hand, overextended, possibly blown their CO power (a one-turn, generally attack-oriented stat boost) prematurely. It’s go time. You activate your own CO power, strafe their front line with artillery, spearhead through the rubble, and fold your opponent into a scattered rout. These moments are fantastic, but the tolerances on them tend not to be all that tight because—unlike with the Vek—the only thing you can do to an enemy unit is reduce its hit point total from ten toward zero. As a result, combat diversity comes from those tactical triangles rather than the elements, which puts the focus on the composition and exposure of your forces as opposed to the precision and timing of your commands. In Advance Wars, your army is a mobile dam plugging and poking holes. In Breach, your crew are three lockpicks in a cylinder full of Vek-shaped pins, tapping them into place.

This difference in the delicacy of the dance informs all the action in these gaems, but let’s focus on the starkest differentiator: the moment before things break your way. Breakthroughs are the lifeblood of Advance Wars, but they aren’t the whole experience. Most of the early gaem is a land grab with the occasional recon skirmish and the mid gaem tends to be skittish between scuffs because you don’t want to end up as the routed player in that best-case scenario. The gaem rocks between denouement and clash, positioning and striking. This is the style, and in context it works well, but it means you tend to see the big moment coming. Troops accrue on the battlefield and serotonin wells up in your skull in the lead up to dropping the hammer. There might be some anxiety but there’s no mystery five seconds before you make the call. What does the moment five seconds before a breakthrough in Breach feel like? Like you’re falling out of a plane, yanking desperately on a stuck parachute cord, coming to terms with how many of your bones won’t work when you hit the ground. Can I be okay losing two cities this turn? Do I really need the time pod AND two working kidneys? Then, in a flush of adrenaline, you remember that fire damages units before they attack, shift your mech one more square to the left, the parachute deploys, and you’re suddenly the greatest genius who’s ever played a video gaem. It’s a hard shift, it’s glorious, and it wouldn’t be possible without a compact board and a delicate, spatially deterministic rule set like Breach has.

So do we have it? Is Breach about the sudden onset and fulfilling execution of deterministic plans? Let's make one more stop to bring out what makes Breach the gaem it is, to extract the tick from the clock. What better place to do so than in the shadow of its linear ancestor?

Reference gaem number 4: FTL.

FTL is homage to the flight deck on a dozen late 20th century sci-fi TV shows. You play the captain of a mixed race spacecraft, in constant retreat from the rebellion vacuum to the left side of the star map as you collect scrap, moral debt, and hull damage. Don't let the chipper soundtrack and artwork fool you: this is a pixelated space tragedy where you will frequently succumb to the rancor of the void and, on consideration of the backstory, you’re probably not even the good guys to begin with. It’s also one of the best video gaems, end of sentence.

FTL and Breach were made by the same team, both share a cynical low-resolution backdrop in a sci-fi universe, and there's general consensus both gaems are very hard. Where it concerns Matthew Davis and Justin Ma (the heads behind these titles, now without question the finest duo in the industry to my mind), comparing the absolute quality of the two gaems they’ve made is completely fair. A Subset gaem is worth your time, money, blood, sweat and tears. But why, specifically, are they worth those things? This is the five thousand-word question. Matt and Justin envisioned FTL as a Kickstarter side project and knocked it out of park in such a way that any subsequent title from the studio would be judged against it…harshly. If you describe Breach by comparing it to FTL, you’ll inevitably compare it as a form of legacy. These two gaems—father and son—are not alike. However, it’s now time for them to trade blows and, with groundwork in place, we’re prepared to chart that confrontation.

FTL and Breach are both a web of interconnected systems, but they aren’t wired the same way. If a missile punches a hole through your shield room in FTL, the proximate effect is a loss of hull integrity. That’s only T-0:00 for the problem, however: you’re now more vulnerable to laser fire, crew staffing that room are injured, and oxygen will start leaking out if you don’t patch things up rapidly. Every Breach map has enough cities on it for you to lose the whole shebang from full power, but taking a hit doesn’t have cascading effects: a city falls, a bar in the grid shorts out, and play continues. You don’t have to do any patchwork to stabilize the remainder of the grid. Breach’s systems are the tools keeping you alive; FTL’s systems are trying to kill you. There is a continuity from a problem now to problems later on the spaceship, but the fight on the ground is self-contained…every turn an almost hermetically sealed unit of struggle.

In FTL, once your ship leaves the hangar, you receive not one crew member, weapon, or point of damage without cross-reference to a probability matrix nested in the code (beam weapons notwithstanding). The gaem is unfair to a degree most developers would balk at. As you play and lose the gaem over and over again, you can come to see enemy ships as a relief because at least they have tangible things like weapon systems you can knock out, unlike the text-based giant spiders at every otherwise vacant jump point (who, in case it’s not clear, are no joke). I’ve played FTL more than anyone really should, having crushed the rebellion with every ship on both PC and iPad. I’m an organic actuarial table for FTL on some level, but I still don’t bat anywhere close to 1.000. Some runs are destined for failure, and you spend 1 to 3 hours wondering whether it will be by catastrophe or suffocation. The range of motion over this story arc is wide and violent. You can spend the first sector of eight in constant peril, trip over a weapon pre-igniter, dominate the next dozen ships, then unceremoniously explode because an ion storm knocked your shield out for two seconds too long. FTL’s urgency oscillates from 1 to 9 and stops erratically everywhere in-between. Breach applies a vise grip that never relaxes below a 4. Unless you contrive such a thing, there are no breathers once combat starts. There are always more Vek coming, and if you block or kill too many in a turn their spawn rate will overcompensate on the next one. Every turn is a puzzle, some more challenging, but never entirely absent. Just as importantly, however, things never really get up to a 9 either. This is because Breach doesn’t have…one of those.

When you play FTL the first bunch of times, you're too busy navigating the perils of an unforgiving galaxy to comprehend (even remember) the real mission swimming around the last sector. Then, one day, you manage to fail your way into Sector 8…and there it is. After fighting modest merchants and pirates for so long, the Rebel flagship covers half the screen and its arsenal rains misery from word one: four guns, four shields, cloaking, hacking…the works. In a gaem crammed with daunting hurdles, it’s amply harder to take down than anything you’ve seen so far and if you manage to take it down, you then find out about (spoilers) its second drone form. Then (spoilers) its third supershielded form. That fight is the 9 missing from Breach. The Rebel flagship is one of the cruelest final bosses in modern video gaming, not because it’s particularly difficult (though it is) but because it keeps the gate on such an arduous journey. FTL is challenging, unfair, and long for a gaem without checkpoints. When the flagship tells you and your afternoon of clutch decision-making to fuck off the first time, FTL hits an inflection point. The Captain Kirk simulator evaporates and you’re left with one thought: how am I supposed to beat that thing? Your next run suddenly has no meaning outside of that question. It's a Neo-seeing-the-Matrix type moment, and many players hated it.

Subset took this feedback to heart and didn’t give Breach a real final boss. It's got a two-stage fight on a volcano against the same enemies you've been dispatching throughout the gaem. What's more: you can choose to start this fight after completing only half the world map, and the fight scales with your progress to be roughly the same difficulty no matter when you choose to take it on. De-emphasizing the last leg of the journey addresses the flagship complaint but it also flattens the curve of a playthrough. There is next to no intensity schism between the first fight and the last in Breach (in my experience, escaping the first island is actually more of an ask because you're having to rely on poorly equipped mechs). The gaem is climactic turn-by-turn, with substantial portions of your global health bar at risk constantly rather than at pivotal junctures. Even the fanfare in the final sequence is slight: the most world-weary of your four NPC allies delivers a bomb, your crew warps out to save another timeline, the bomb blows up noiselessly as you watch from space. The runs blend together, island-by-island, map-by-map, turn-by-turn. In the end, my aim to divorce the medium from the message must fail, because Subset fused them together. You as a player and your pilots as fictional characters are both under the thumb of infinite, iterative time. Ludonarrative cyclicity.

That feels like a recipe for hopelessness, doesn’t it? Borderline nihilistic? Not so. This is the magic in Breach’s design: every moment matters. There’s no random disaster waiting to befall your soldiers when they fuck up a shot. There’s no one sitting across from you, shifting tactics to keep you off-balance. There’s no ebb and flow in the scale of the conflict. There’s no master test of your skills at the end of the sector. There’s just this one turn, with three mechs and three moves, a complex terrain and a puzzle to solve with as much time as you need to solve it. If you fail, it might be the end of the world, in which case you’ll just have to start again. If you succeed, however, you are a savior, rewarded instantly not with violence but with temporary peace and quiet across the land.

Is Breach better than FTL? It is not. Like the Federation cruiser on its first brush with the flagship, Breach might be special but when I went back to FTL for reference the hole that gaem drilled in my heart sent Breach back the way it came in short order. There’s more than a bit of magic in that experience too. So alas, Subset accidentally set a bar so high they couldn’t clear it. Seems life’s not fair, even to video gaems. Thankfully that’s okay because Breach, at its best, is like life’s beautiful moments: ever-present, easy to miss, clutch and fleeting. No strategy gaem I’ve played delivers those moments as often.