Newton’s third law of motion states (idiomatically at least) that every action has an equal and opposite reaction. When this idea is combined with the limits of personal subjectivity, a simpler assertion arises. A chain of events, however inscrutable, produces every outcome—an exact combination of environment, habit, and of course fate. Account for these.

Do you? Does anyone else? Why are you doing this thing this way, as opposed to any other way or thing that could be done?

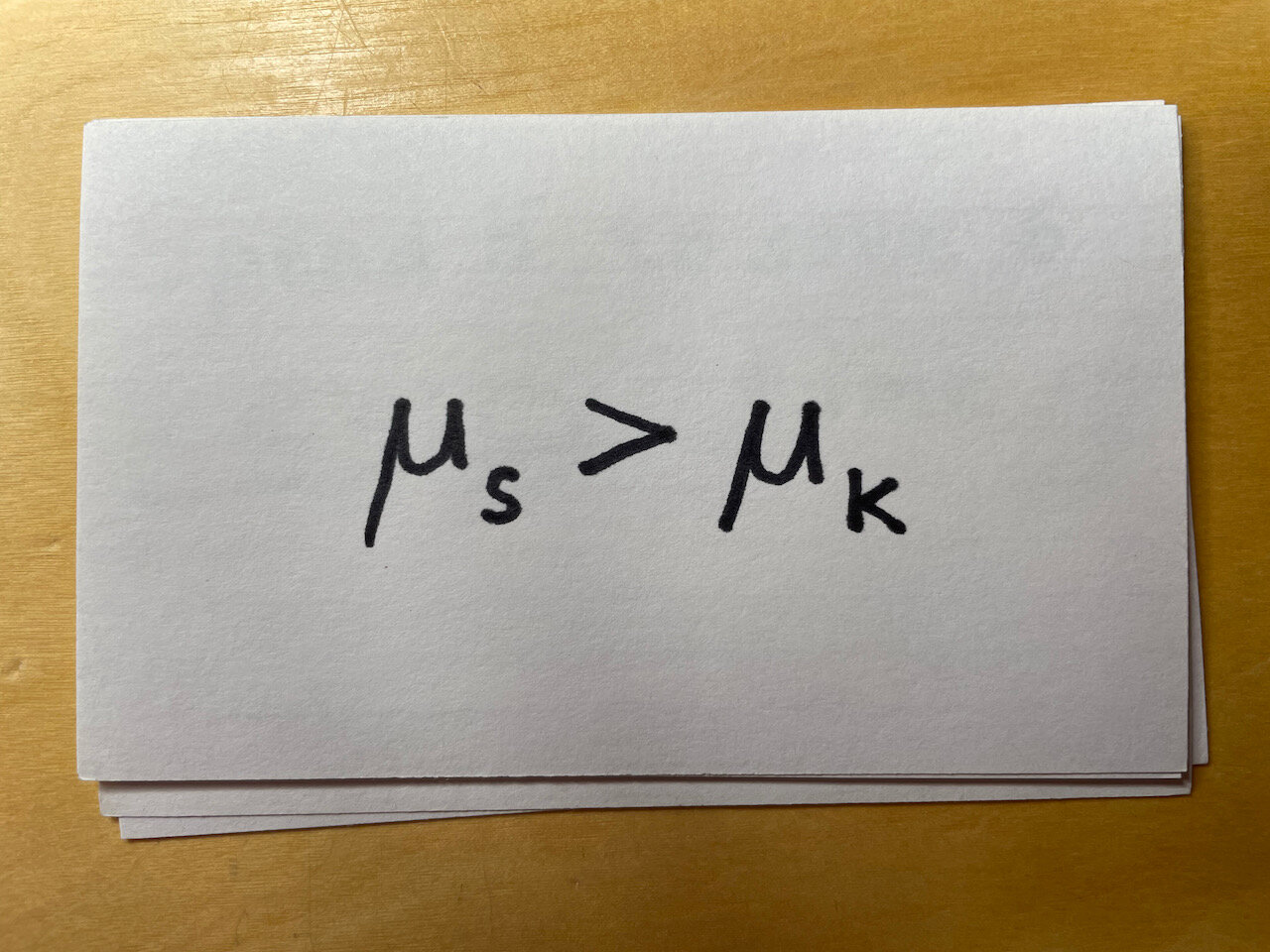

An action-oriented variant of the apprentice’s mantra: "first you get good, then you get fast”. Also see the military logistic’s adage: “slow is smooth and smooth is fast”. Speed is a byproduct of competency. It should only be forced under duress.

An adapted quote by Thomas Huxley about the “most valuable result of education”.

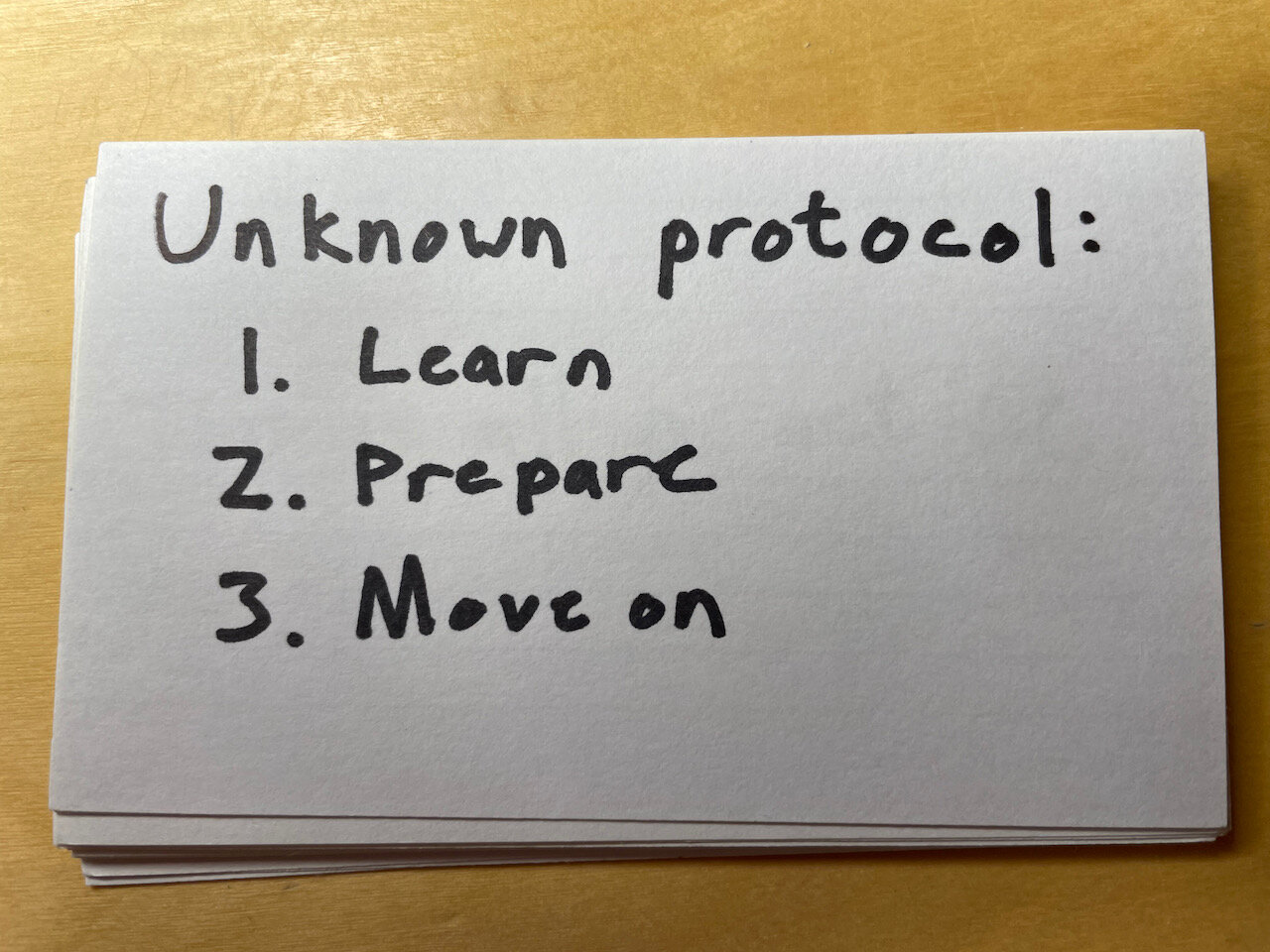

1. Learn. What about this unknown is, in fact, knowable?

2. Prepare. What about the remaining unknown can be mitigated or exploited?

3. Move on. The rest is out of your control.

You do not know what tomorrow will bring. All you can do is prepare. In fact, all you will do is prepare. But how?

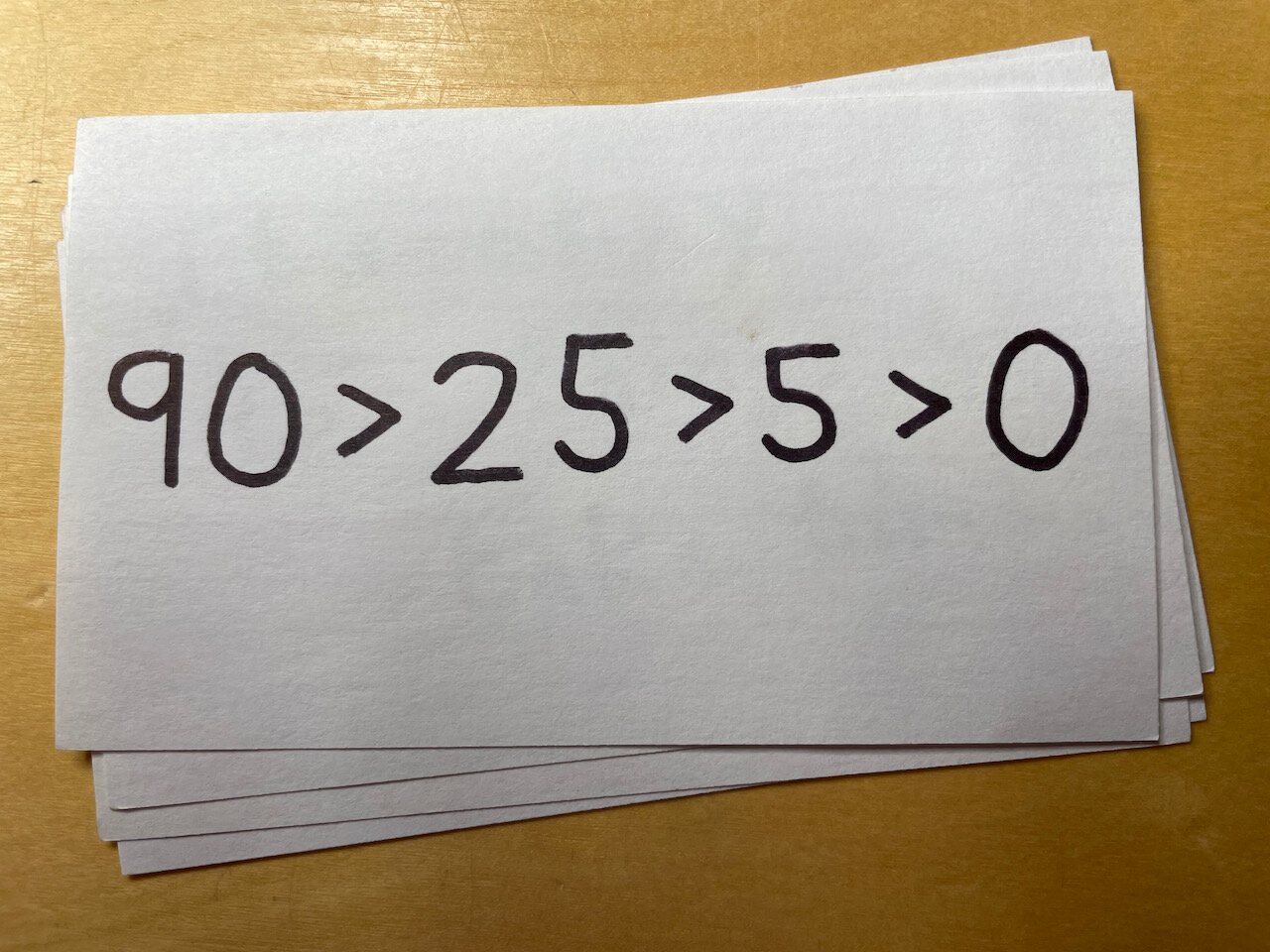

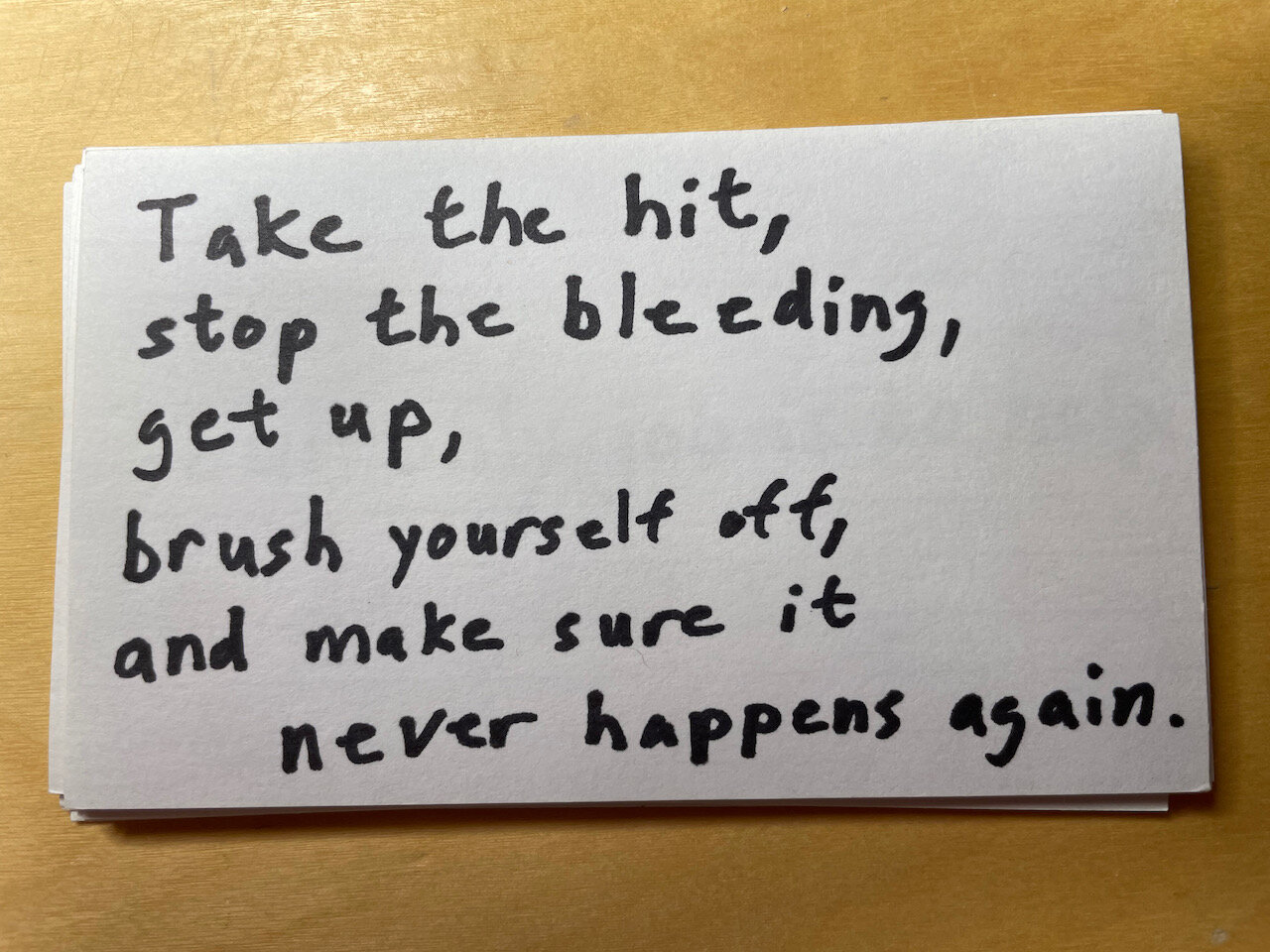

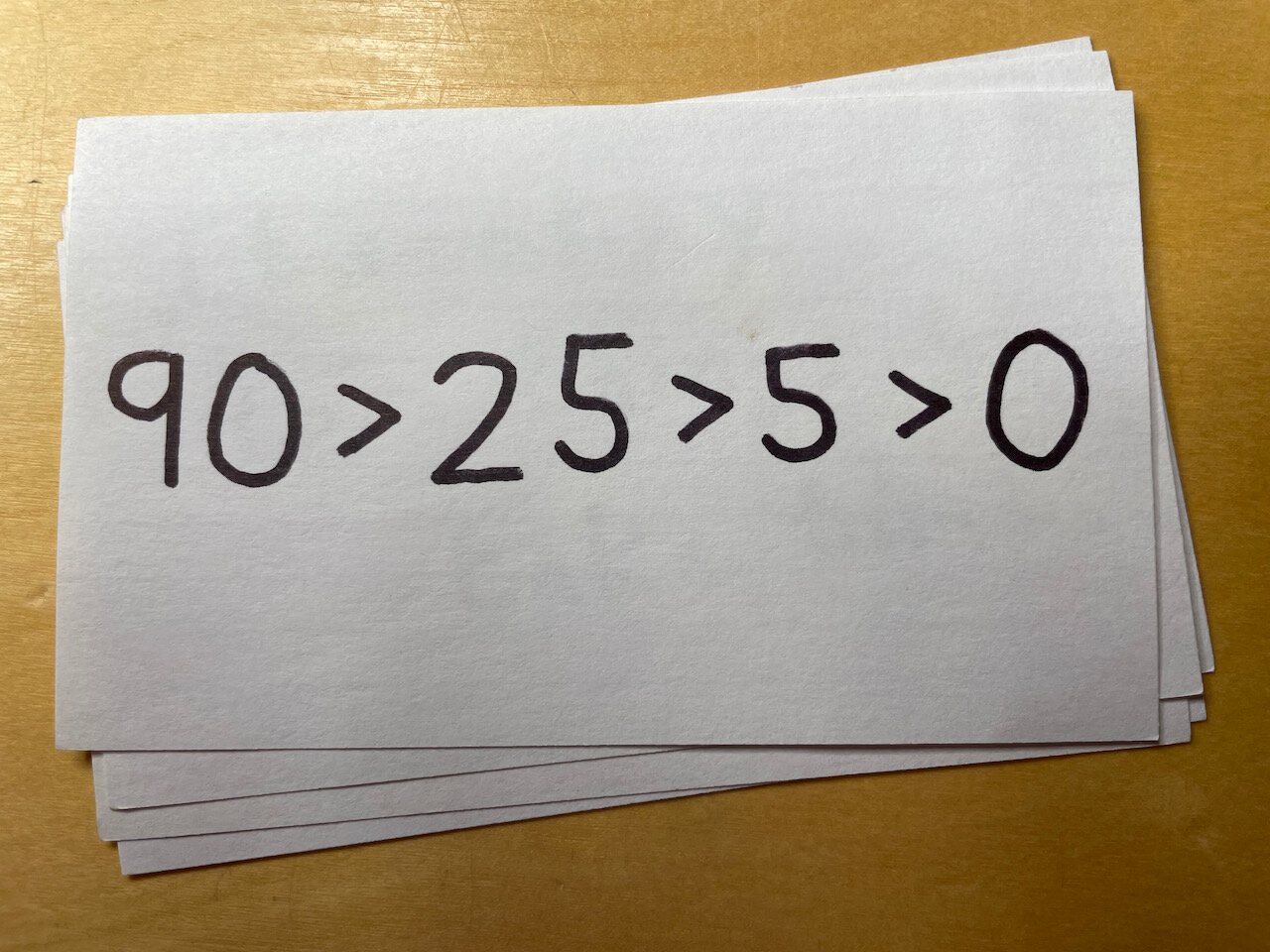

A basic triage script. Written out further: consciously absorb the trauma, deal with any escalating problems, assess the situation, recover as best you can, and document the cause for future prevention.

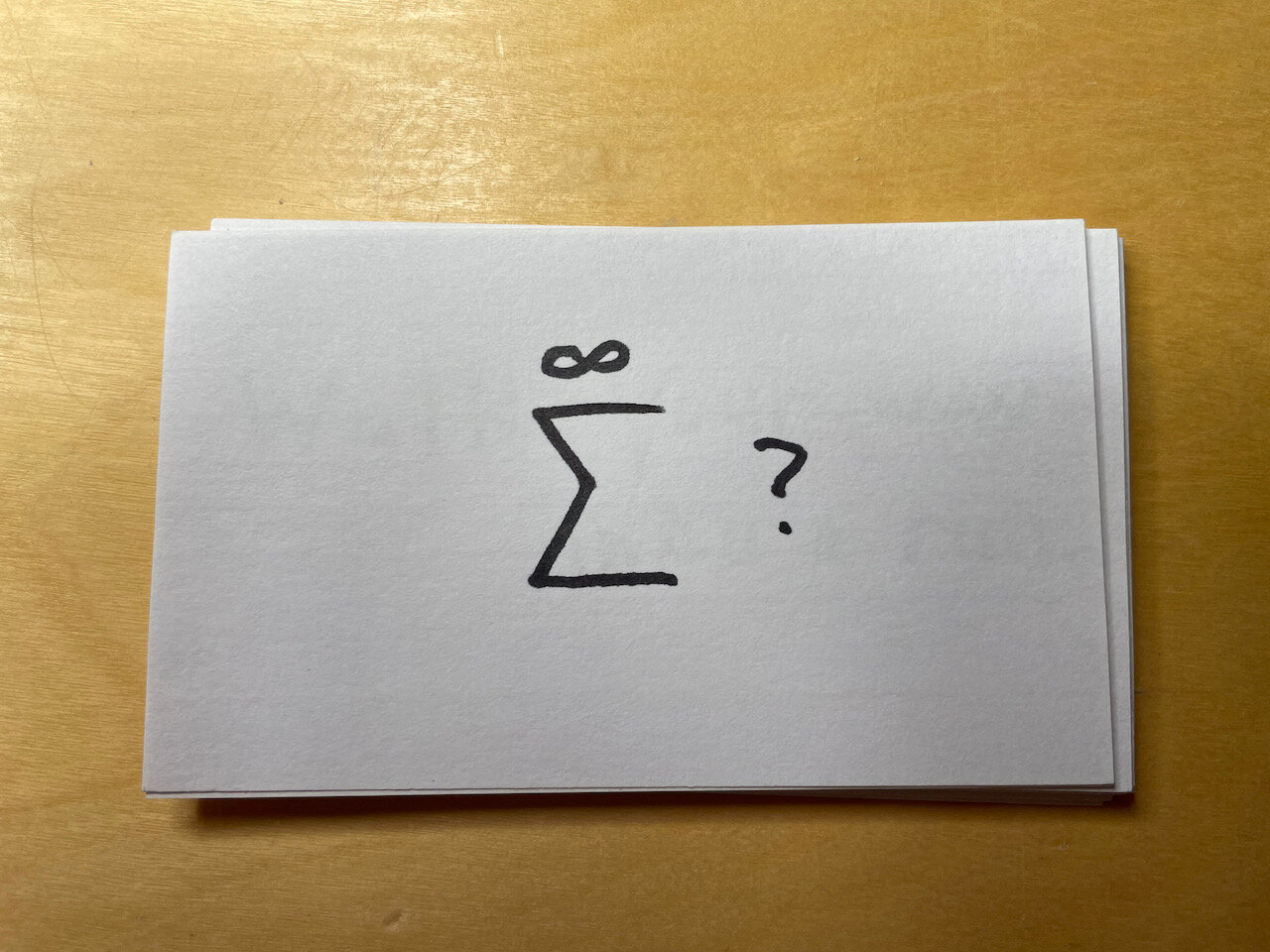

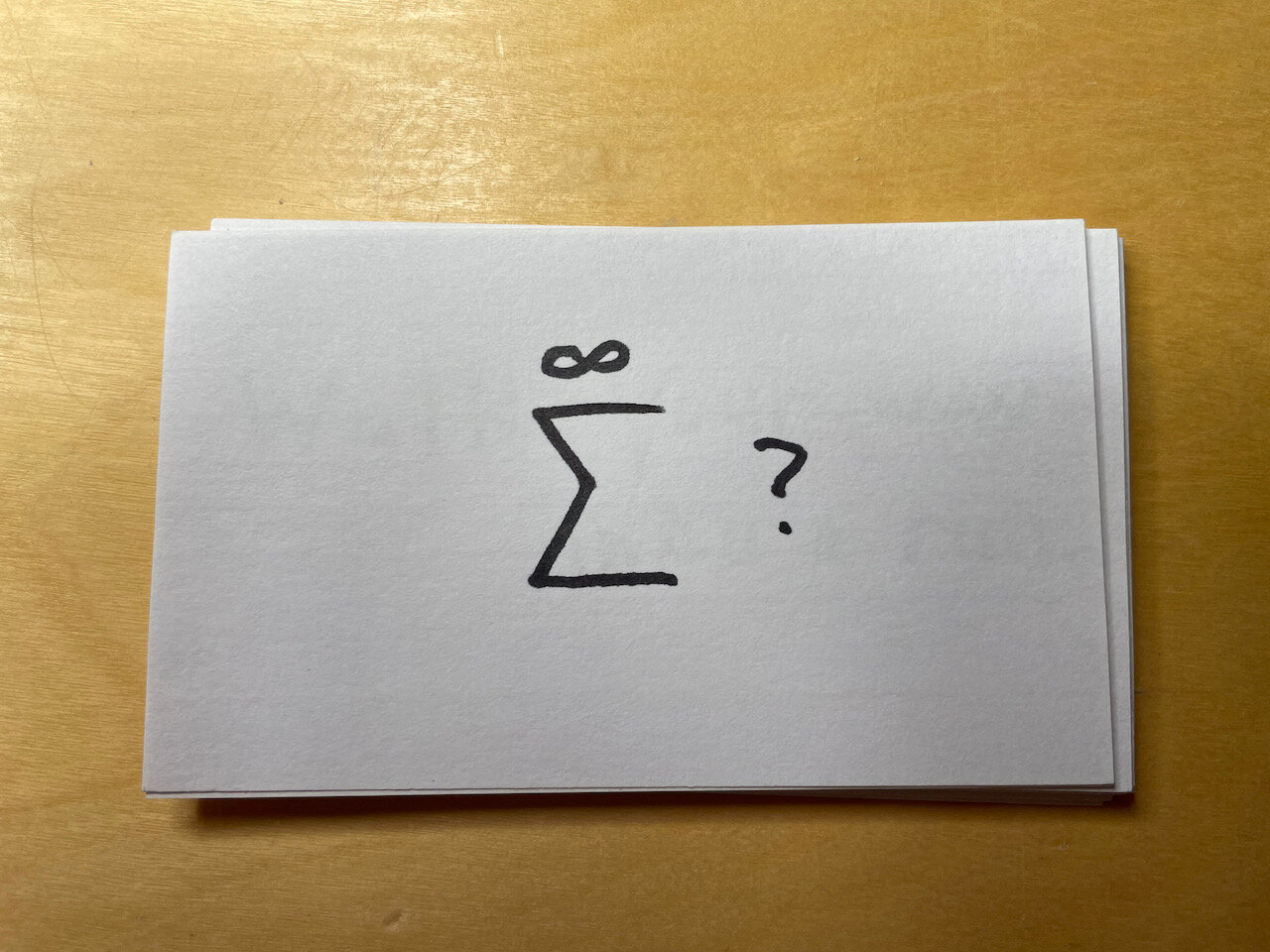

What does this action amount to, ultimately, across all time and space—every person it will touch, every thought it will provoke, every event it will trigger? What does it add up to?

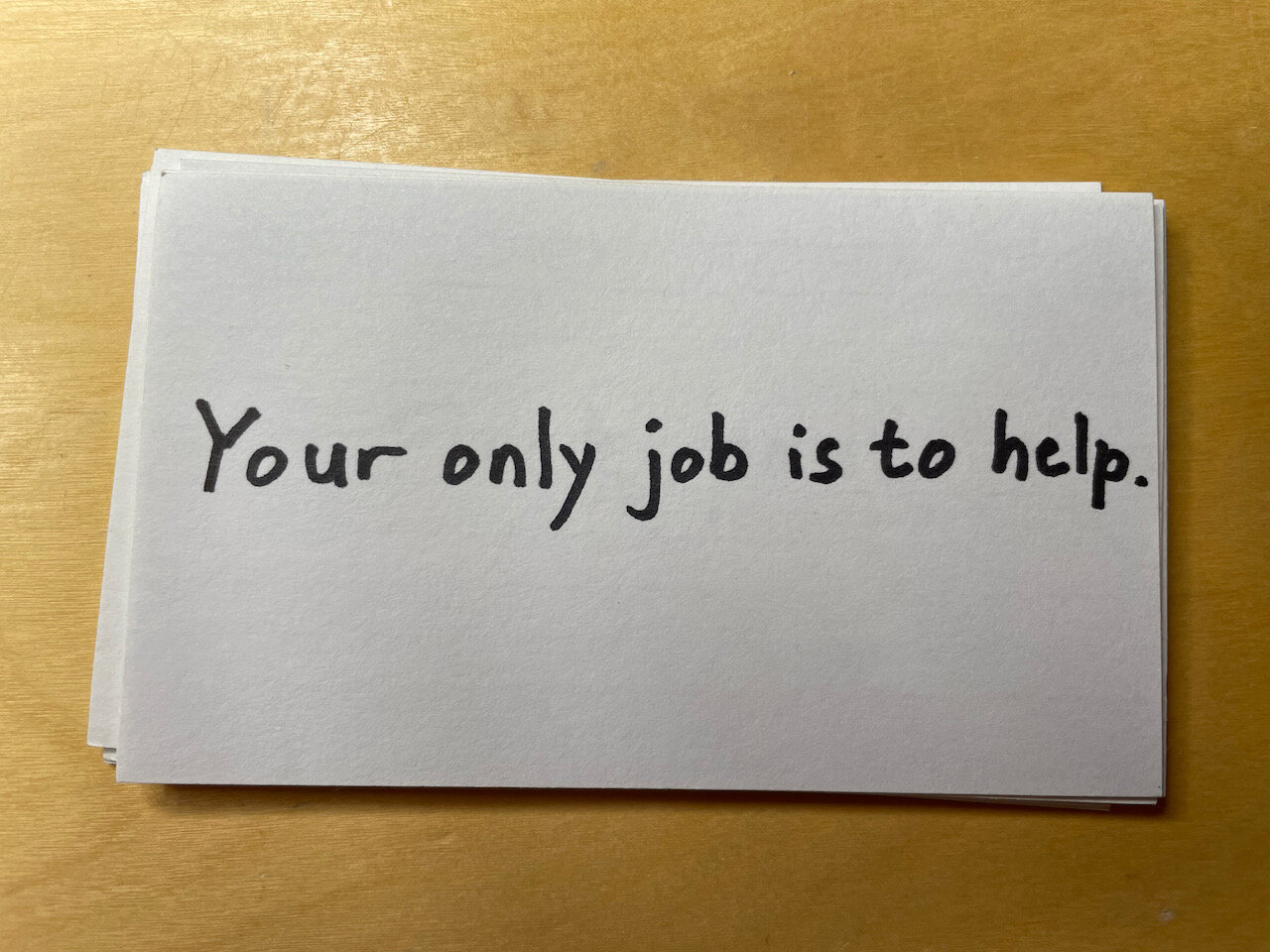

You’re a set of hands in a procession. The world is not resting on your shoulders. Do what you can.

Self-explanatory.

It’s really easy to cop out of a magical moment, mostly because that’s preferable to fucking one up. Likewise, it’s tempting to scoff at a moment in the making, out of fear you become an idiot for buying into a false one. The only problem is life becomes irrelevant without those moments. You have nothing better to do than gamble on them.

A lot of psych literature recommends against comparing yourself to other people. This is stupid advice. Compare what you do to every conceivable measuring stick. You’ll get tired of the impossible and discouraging ones pretty quickly, leaving you a more intelligently calibrated grasp of where you are and what you’re trying to achieve.

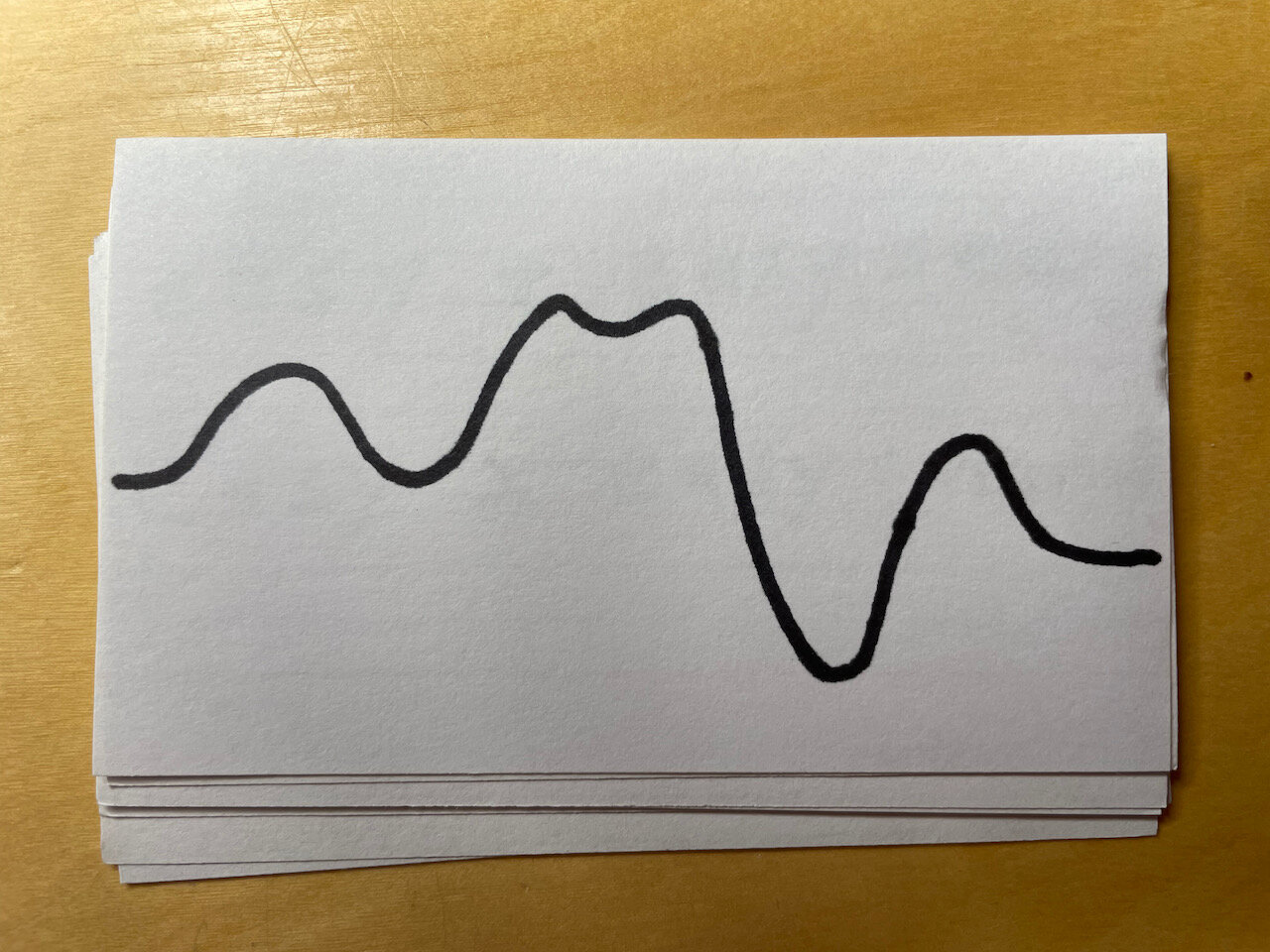

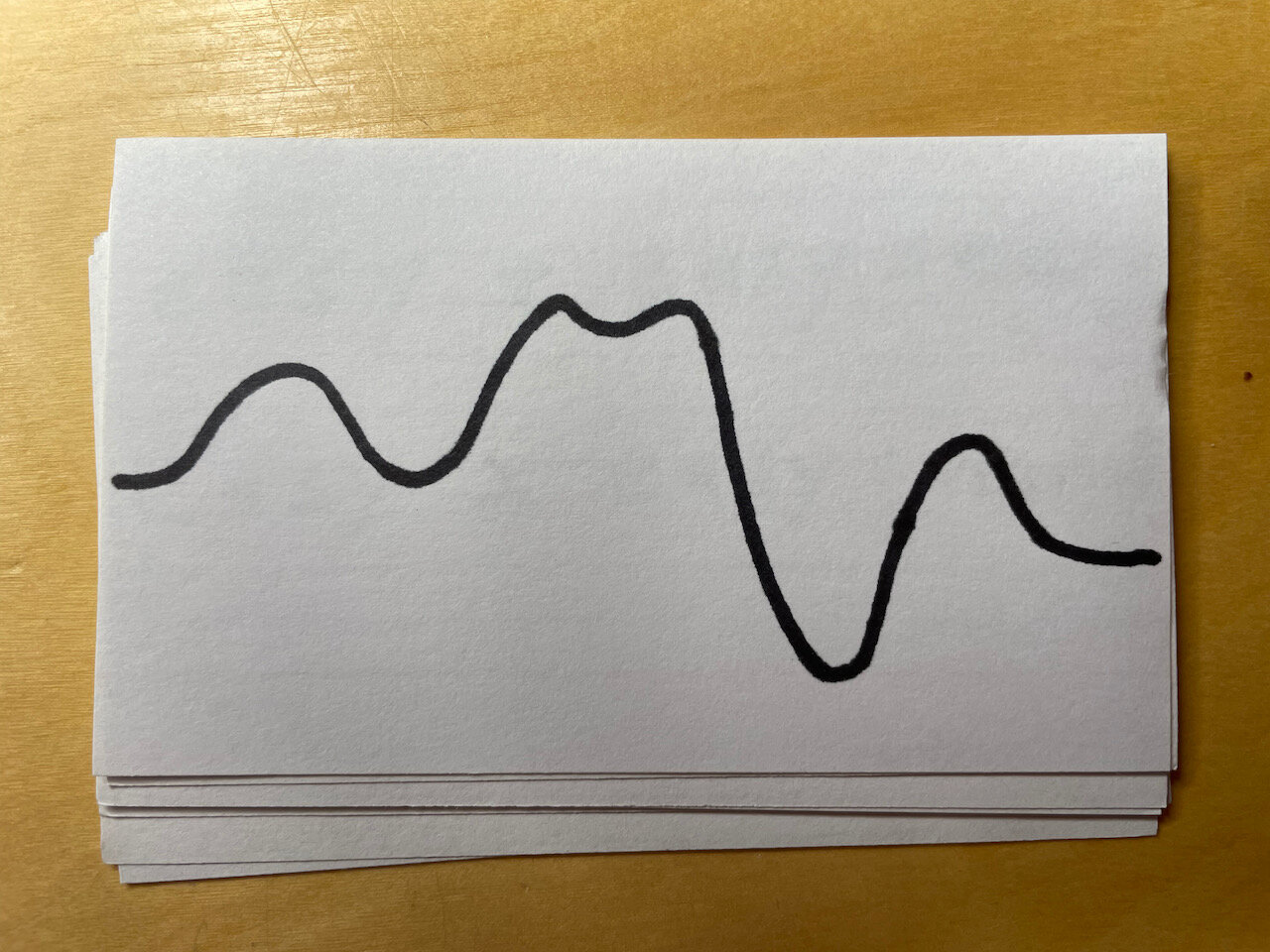

X-axis is possible methodologies and y-axis is their efficacy. All the way on the left you have your basic bell curve: a little optimizable space. As you move right, you dip into the indecision matrix of splitting between two strategies until you emerge in the superior one. The superior strategy is bimodal, indicating two conflicting but equally useful approaches both undergirded by an effective general principle. Approaching from the right we have an Erlangian curve that promises rapid improvement to its apex and a massive loss if we stray from it too far, but notice that even the most optimized form of the right-side strat is only barely better than the worst implementation of the left-side one. These analogies apply far more often than you would think. Strategize, then optimize.

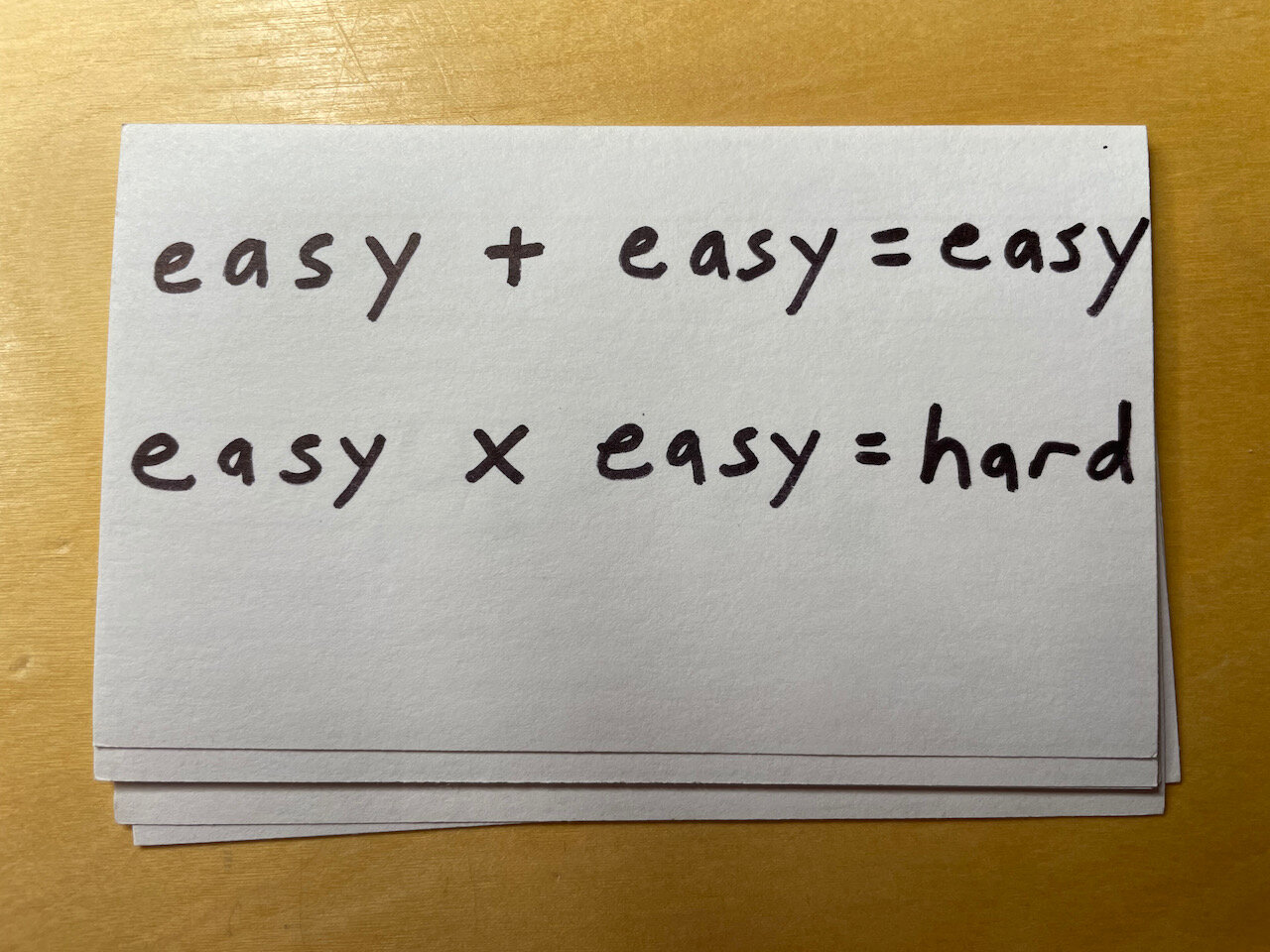

It’s easy to do any number of easy things in succession. They only become hard when you do them simultaneously. Understand and do what you’re capable of.

Start moving.

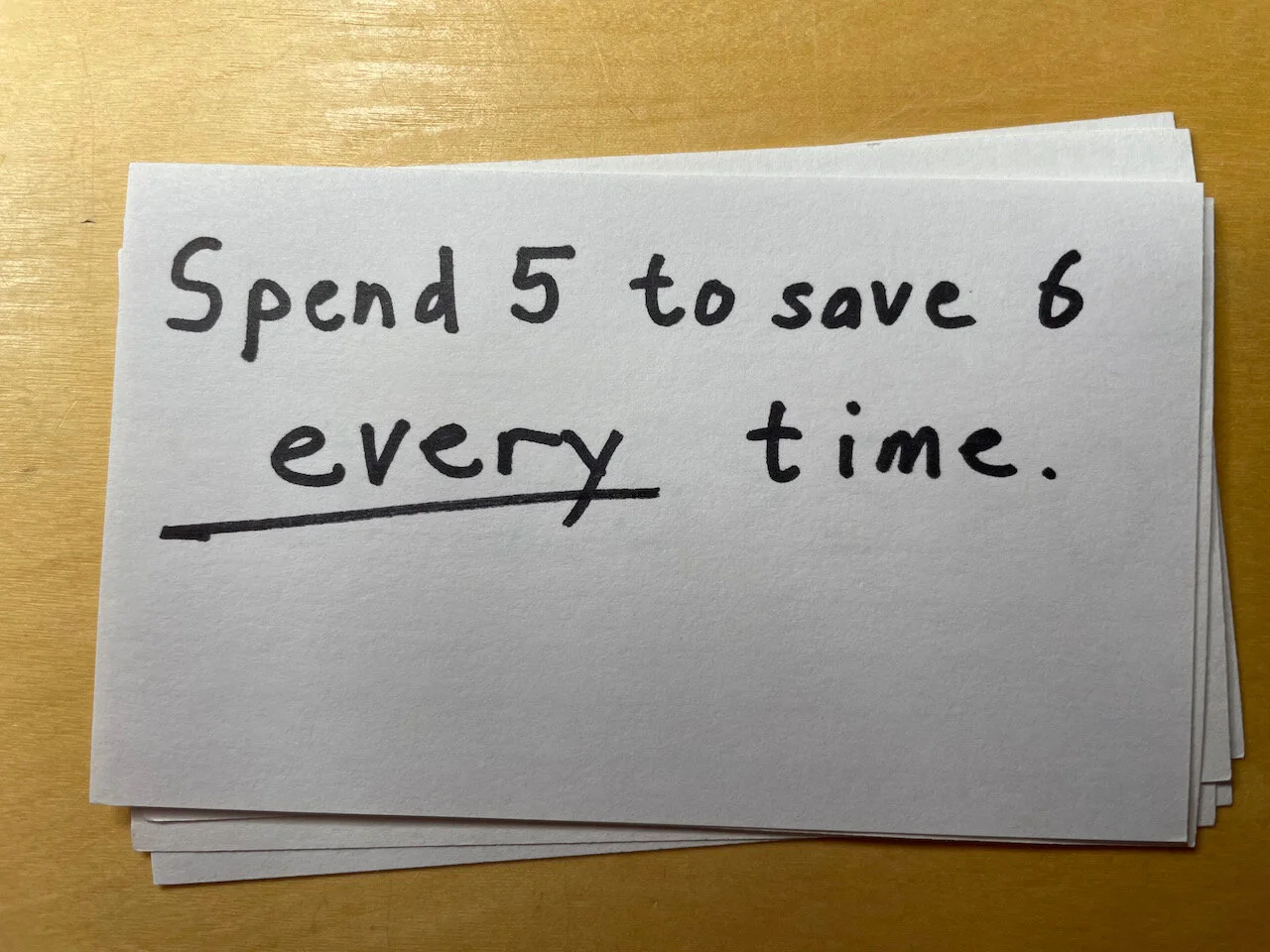

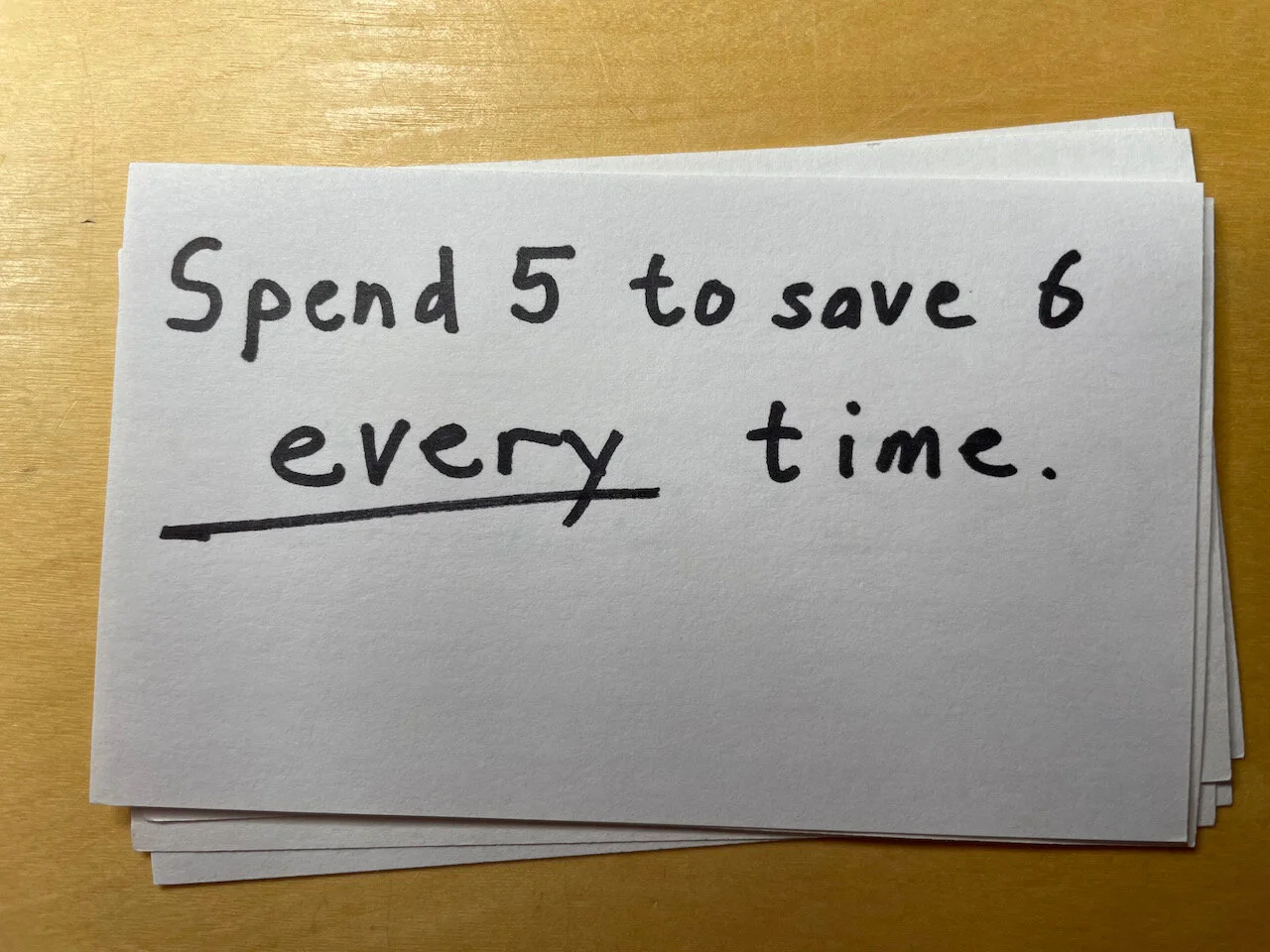

A lot of times, it takes hard analysis to decide whether something is worth doing over the long run. Principles of discounting and opportunity and marginal costs abound. Here’s one you don’t have to think about: 20%. If you’ll get a free 20% out of doing something, just do it. It will be worth the hassle, promise.

The more you can do, the better. But for god’s sake: do something.

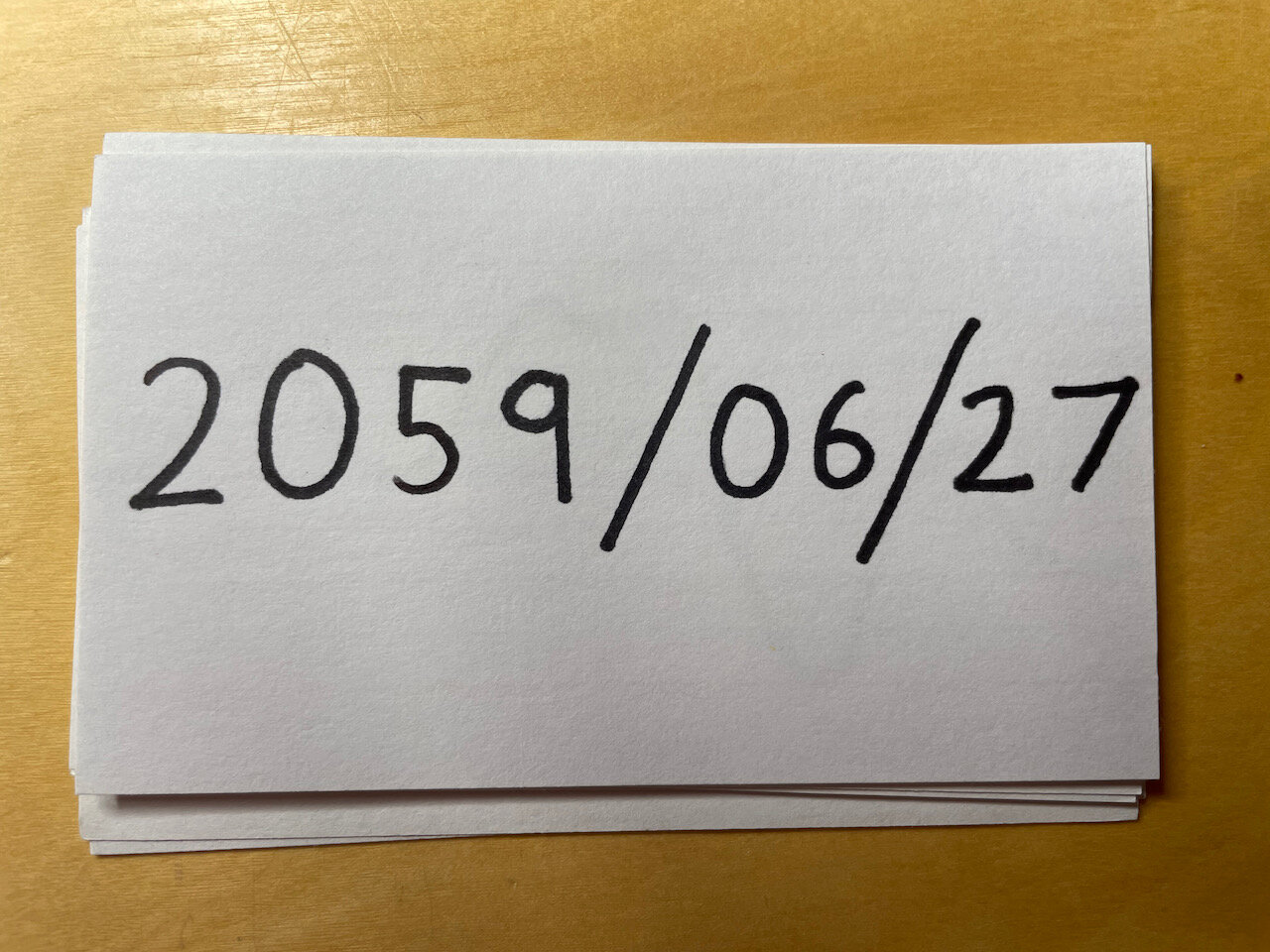

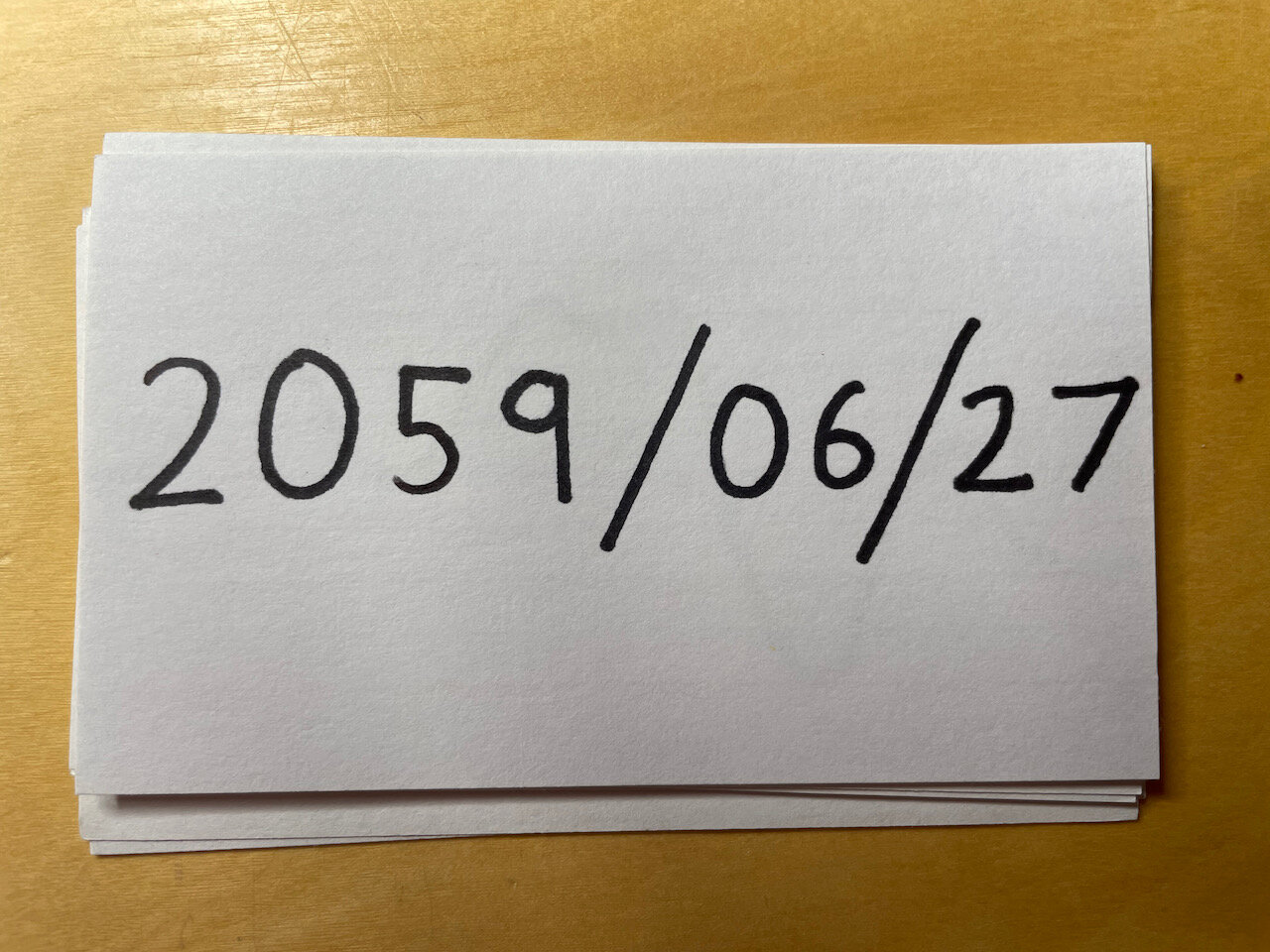

The day I turn 70. A day when most of the people I know and care about will be dead or seriously diminished, including myself. It’s coming. Act like it.

A lot of the time they do! You’ve got a bunch of it left. Spend it judiciously, but spend it.

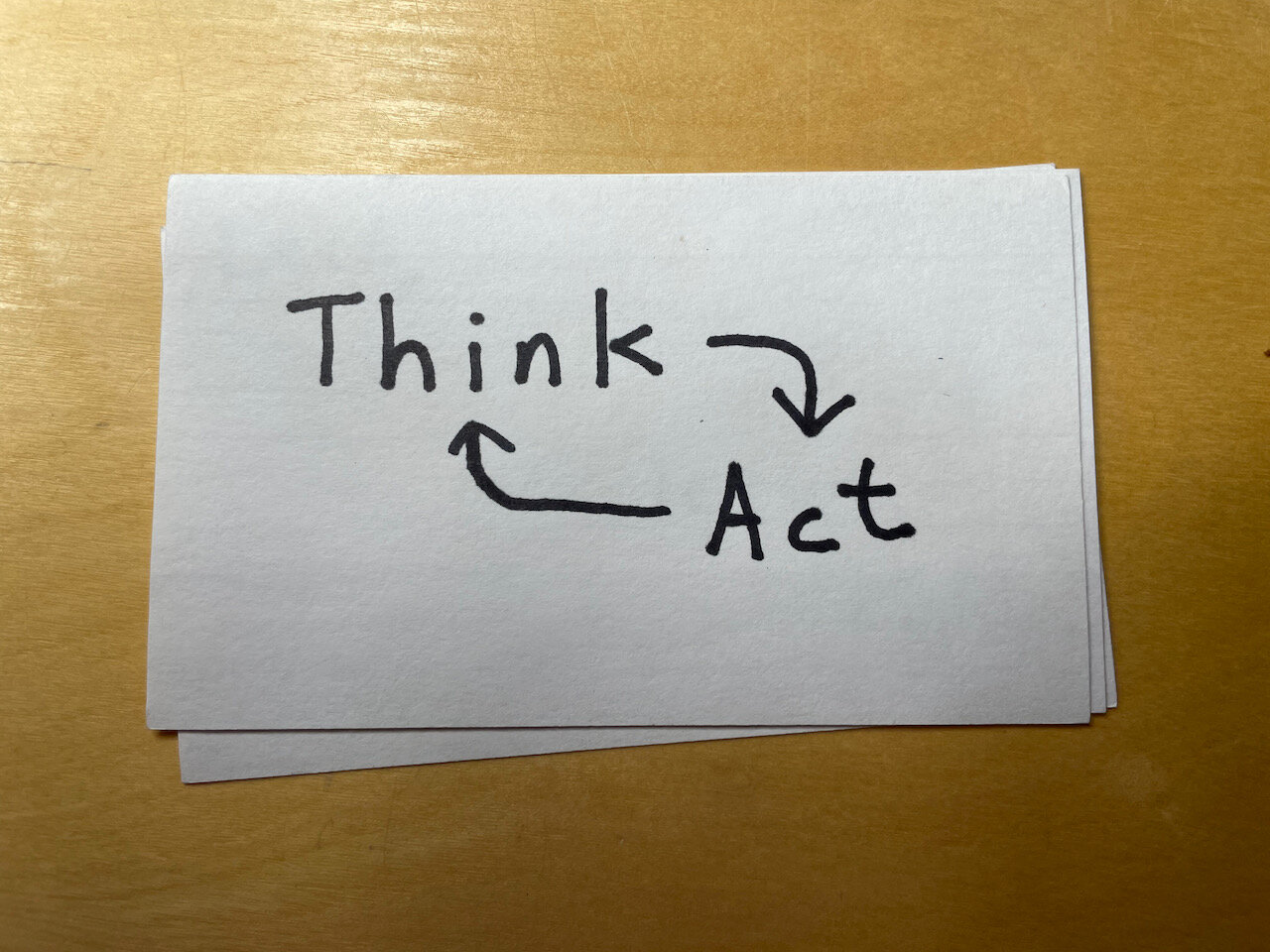

When you have an idea, test it. When you come to a crossroads, reflect on it. Thinking makes acting easier; acting makes thinking easier. Switch.

There’s like a thousand sayings underneath this one about mountains and foundations and planting trees. Put in the work, one foot in front of the other.

Every issue worth caring about can be broken down and traced back to a conceivable set of steps, however challenging they may be to climb. Fractal problems should be identified and judiciously ignored.